tl;dr: a message to myself, and to incoming CS undergrads.

even if impostor syndrome hits hard, you’re all smart and competent people. and you’re now smart and competent enough that everyone wants a piece of your potential.

there’s a whole ecosystem of people with financial stakes in shaping your career choices, ready to sell you compelling stories about what you ‘should’ do with your life. and it’s surprisingly easy to absorb one of these narratives and mistake it for your own beliefs.

don’t get stuck in flatland: there are far more possible career paths than the options being marketed to you, and you’re more than capable of figuring out what’s actually meaningful to you and pursuing it.

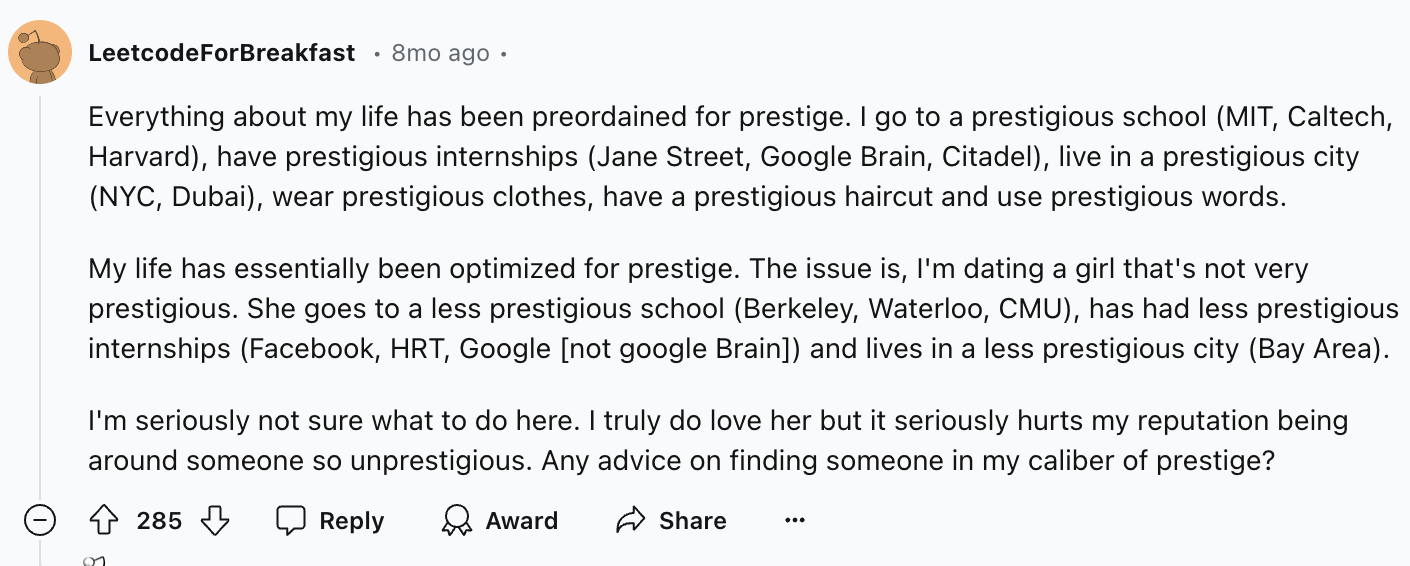

(apparently I need to make it clear that this is satire. source: reddit)

(apparently I need to make it clear that this is satire. source: reddit)

subcultures as planes of legibility

I’ve just finished my undergraduate degree at Cambridge, where I studied computer science.

for us computer scientists, our world has a bunch of scenes, often (but not exclusively) mapping onto career trajectories: the quantitative traders, the entrepreneurs, the corporate software engineers, the researchers, the makers, the open-source hackers.

one way to characterise a scene is by what it cares about: its markers of prestige, things you ‘ought to do’, its targets to optimise for. for the traders or the engineers, it’s all about that coveted FAANG / jane street internship; for the entrepreneurs, that successful startup (or accelerator), for the researchers, the top-tier-conference first-author paper… the list goes on.

for a given scene, you can think of these as mapping out a plane of legibility in the space of things you could do with your life. so long as your actions and goals stay within the plane, you’re legible to the people in your scene: you gain status and earn the respect of your peers. but step outside of the plane and you become illegible: the people around you no longer understand what you’re doing or why you’re doing it. they might think you’re wasting your time. if they have a strong interest in you ‘doing well’, they might even get upset.

but while all scenes have a plane of legibility, just like their geometric counterparts these planes rarely intersect: what’s legible and prestigious to one scene might seem utterly ridiculous to another. (take, for instance, dropping out of university to start a startup.)

we’re all stuck in flatland

I sometimes have undergrads asking me for career advice. they tend to ask questions about what they ‘should’ be doing, or how they can do it better: what do I need to do to get an internship at $BIG_CORP? how do I get a first-author paper at a conference? is it better for me to go into quant trading or software engineering or research?

rather than answering their question directly, I like to poke at what makes them feel they ‘should’ do the thing in the first place. what motivates you? why do you do what you do?

I’m always pleasantly surprised by how willing they are to engage with this. but more often than not, they say something like “of course you need to do X, that’s just … the thing we’re meant to do at this stage, right?” and when I poke at this a bit more, they often realise they don’t actually have an answer for ‘what motivates them’ that they themselves feel satisfied with.

the claim I’d make here is that many of these undergrads are stuck in flatland. they’re operating within some plane of legibility, adopting its goals and markers of prestige, maybe occasionally acknowledging the existence of other planes at points where they intersect. but they never quite realise that the plane they live in isn’t the only plane in the world — and, importantly, never explicitly make the choice to inhabit that particular plane as opposed to any other.

(yes, I fell victim to this myself. as an undergrad, a lot of what I chose to do was — and, in some ways, still is — constrained by the planes of legibility of the scenes I was surrounded by back then. and in part this essay is a letter to 19-year-old euan, who really ought to have known better.)

”… one way you know that something is an institution is that you don’t have to give reasons for it. Getting a college degree, like getting married, is what people do.” ~ haquelebac

stumbling into a plane

so what makes people enter a particular plane in the first place? in large part, it’s mimetic: we come to desire what others desire.

when you get to university you’re confused. suddenly no one’s telling you what you’re meant to do with your life. the last hoop ‒ getting into your university of choice ‒ has been jumped, and your hindbrain is itching for the next thing. (indeed, when talking to students, I’ve had some even go as far as to say “all through high school, my motivation was to get into Cambridge, and now I don’t really know what to do.”)

and in any case, there are already very obvious paths through very obvious planes. everyone’s looking for big tech internships; everyone’s looking for spring weeks.

perhaps, after a secondary-school-education’s worth of brutal zero-sum competition, the instinctive thing to do is to step into the next brutal zero-sum competition. after all, you’ve learned to win, and if all the big fish are in that one small pond, it must be a really prestigious pond, so the only way to win is to jump into it.

or perhaps you’ve been telling yourself you should eventually make a plan, but thinking about the future is hard, and university life is busy enough as it is: there’s always another problem set, always another lecture, always another social. “and everyone else is talking about that internship; I can’t go wrong by applying as well…”

and so it goes. absent any better ideas of your own, it’s very easy to get swept up into other people’s planes, and into their visions of what you (or they) should be doing: the spring weeks your friends are applying to; the jobs that cool people in the years above you are starting; the career advice you get from your family. you see other people competing for the same prestigious internships and you begin to want them too, not necessarily because they align with the things you care about, but simply because they are what others desire.

you are in a plane, and you probably didn’t get there on your own.

snakes in the planes

so university is already a mimetic nightmare, and we already don’t have much control over the planes we end up in. but what’s worse is that some companies have learned this, and are using it as a recruitment tactic.

for instance, in Cambridge CS (and elsewhere), there is a very strong internship culture. this culture

- (a) makes it seem like doing an internship is the only socially-acceptable way to spend one’s summer,

- (b) disincentivises people from looking for opportunities beyond a standard list of Prestigious Internships, and

- (c) leads to lots of people spending painful amounts of time applying to internships (writing cover letters, grinding leetcode) — often not even because they necessarily want to do the internship, but because this is just the thing that’s expected of them.

to be clear, there are very good reasons for some of this culture to exist: for a computer scientist who wants to go into software engineering, internships provide real-world experience that you just won’t get in an academic environment, and act as a good signal to future employers that your software engineering skills are above some competency bar. but there are many other interesting things one can do with one’s summer besides a conventional internship1 — e.g. doing a UROP, building a nuclear fusor, starting a startup, playing around with crazy type systems, couchsurfing cool projects in San Francisco, convincing OpenAI to start an internship program — and the prevailing culture heavily discourages people from trying them.2

how did this culture get so strong? in large part, it’s being heavily optimised-for by the companies themselves. since university is such a mimetic nightmare, and it is in the midst of this that students choose what planes to inhabit, a little nudging on the part of a company can quickly suck confused students into their plane, and shift their life plans en masse.

notably, a few firms — particularly in quantitative trading — have put enough effort into maintaining presence and visibility in Cambridge that they’ve positioned themselves as both the default option and the prestigious option. they host fancy dinners and high-quality nerdy events, hand out unlimited merch, and sponsor all the technical societies;3 once, they even mailed small care packages of sweets to all first-year CS students just before their exams.

now, from the perspective of the trading firms, this is a drop in the (financial) ocean: the amount spent on Cambridge per year is almost certainly less than the average quant trader’s annual salary. but for the undergraduates, this level of attention on campus is a massive reality distortion field (and talent attractor). consider: trading firms aren’t household names; indeed, very few people had heard of them before starting at Cambridge.4 but once you join, everyone around you is wearing their t-shirts, everyone you know is applying to their internships, you probably applied too, and if you get an offer you’ll very likely take the internship. (I certainly did.)

so what emerges is a profoundly asymmetric market: on one side, confused undergraduates figuring out what to do with their lives, and on the other, corporate juggernauts with nine-figure budgets and precision-engineered recruitment machines. and for the companies it’s an insanely good deal. judging by salaries alone, the best Cambridge CS grads are probably worth millions of pounds in generated value… yet they can often be bought for little more than the price of a fancy dinner and a pack of sweets.

important caveat: I’m not trying to say “internships bad” or “quant bad” or anything like that. (in fact, during my undergrad, I did end up doing both of these things.) what I really wanted to convey here is that these internships live in a plane of manufactured legibility.

in other words, all this is just to say: by all means apply to internships. but just make sure you know why you’re applying — whether for the skills, for the signalling value, for the money, or for whatever other reason — and make sure this is truly a decision that’s good for you, not just for the company trying to poach you. (for many of you, especially those of you with legible signal before starting university, a lot of companies are about to notice you and start trying to poach you. you’re about to be wined and dined and fawned over and invited to many many coffee chats. there is no such thing as a free lunch. you have been warned.)

… so, what should I do with my life?

I have my own views on what I’d like to see more people doing: which planes seem overcrowded, which planes feel neglected but promising. but the last thing I want to do is to tell people what they should do with their lives.

all I want is for people to at least make an informed decision about what they want to do with their lives. to step out of the plane they’re operating in ‒ to leave flatland ‒ and to realise how the things they do could look very different in different planes.

to see the set of all planes, and say ‒ I explicitly want to live in this plane, I explicitly want to adopt its value functions, because these align with the things I care about. (you will become increasingly like the other people in the plane you choose. this can be a very good thing… or a very bad thing.)

or ‒ even better ‒ to go rogue, to never quite settle for any specific plane, but rather to steer a narrow path through their intersections while being mindful of how it projects down into each of them. (note that this does not mean ‘drop out of college and become an autodidact in the mountains’. nor does it mean ‘do all the shiny things in all the shiny fields for maximum optionality’.)

so, where do you go from here? no advice post is complete without its summary listicle, but at this point, providing a step-by-step ‘guide to career success’ would simply be giving a map of some arbitrary plane.

instead, here are a few high-level prompts that might help you escape flatland. (as usual, the law of equal and opposite advice applies.)

- try lots of things. build stuff. research stuff. go to random talks. go to random societies. look at stuff that piques your interest, even if it seems weird or sus or irrelevant or illegible or unprestigious or uncool. (but if it seems sus, try to work out why! do not completely turn off your susness detector.)

- exploration heuristic from patrick collison: “do your friends at school think your path is a bit strange? If not, maybe it’s too normal.”

- try to grok as many planes as possible. what motivates these people? what gives legibility and status in that plane? who — or what — decides who gets it? be a good anthropologist, and talk to people outside your bubble.

- check back later for a (non-exhaustive) list of planes.

- you don’t have to settle or grind (yet). careers are long; you are talented and have more time than you think. don’t sell your soul to a memeplex without understanding the full terms of the contract.

- prompt: “when was the last time I did something that no one else cared about but me?”

- beware of old people with money who want to use you as a missile. as an undergrad, your career path is maximally flexible and your skillset is minimally specialised: you’re a missile that can in principle be pointed at any technical problem. many older people have strong monetary incentives to point you at problems they care about, and to convince you to do things that may not be for you but rather for them.

- in particular: around ambitious young people, there’s sometimes a pressure to rush through life, or cancel all your life plans to jump on opportunities that might not be around for long. beware this contagious sense of panic. and, in particular, beware older people creating narratives of urgency to convince you to change your life plans.5

- all the same, don’t pass up on opportunities to stay legible at low cost to your values. for instance, even if you despise the corporate world, having a big-tech internship will help convince people (funders, collaborators, …) that you know how to write decent software.6

- appearing legible to lots of different planes at once can also be useful. if done well, it also has the advantage of forcing more exploration.

- be a pragmatic idealist. it might hurt to admit defeat in the face of Institutions, but not all battles are worth fighting. save your energy — and credibility with Institutions — for the ones that actually matter.

- and remember that everything is a plane. there’s a co-working group I used to run at Cambridge, for students to work on their passion projects. it’s still one of my favourite planes (and one of the most self-aware) — but it’s still a status game, where (a harsh caricature of) the high status play is “to be unconventional, to have disdain towards quantitative finance, and to be doing side projects that look complex, intellectual and not too clichéd”.

- (this essay is also a plane.)

- above all, trust your gut (insofar as it isn’t blatantly trapped in a plane), and break any of these rules sooner than doing anything outright barbarous.

appendix

related links

- Violence and the Sacred: College as an incubator of Girardian terror

- Taste games

- Even artichokes have doubts

- Patronus

- College advice from Patrick Collison

- Finance, consulting and tech are gobbling up top students (The Economist)

- School, Home

- Taste games

- College advice for people who are exactly like me (Ben Kuhn)

acknowledgements

this post is in large part drawn from a very insightful conversation I had with David Yu, the organiser of SPARC — if the ideas here resonate with you, you’ll probably like the program (or its European versions).

almost all the inline links were courtesy of Gavin Leech, who continues to have impeccable taste in blogposts.

thank you also to everyone else who helped shape this work, either through their past writings or their direct feedback: Malaika Aiyar, Penny Brant, Xi Da, Lucy Farnik, David Girardo, Uzay Girit, Minkyum Kim, Jinglin Li, Dylan Moss, Adithya Narayanan, Lydia Nottingham, Abdur Raheem, Agniv Sarkar, Martynas Stankevičius, Daniel Vlasits, Dan Wang, Jack Wiseman, Eric Zhang (in alphabetical order)

Footnotes

-

these are all real examples of things my friends have done over the summer ↩

-

so much of this is about defaults! nudge theory is powerful: people rarely look beyond what’s presented to them upfront… ↩

-

this one is particularly insidious. often, well-intentioned sponsorships officers accept strict exclusivity clauses and branding / promotion requirements in order to get a few thousand pounds extra for free pizza at society events. but at some point, one has to ask — at what point is ‘free’ pizza outweighed by the costs of a few companies monopolising student mindshare? ↩

-

though apparently this is starting to change, as the maths olympiads are now sponsored by quant trading firms… ↩

-

you might feel that some problems are urgent and important enough for you to cancel your life plans and work on them right now. this may be true! but if this is indeed the case, let it be something that you determine for yourself, rather than something that Older People pressure / scare / coerce you into doing. ↩

-

whether it always implies the ability to write software is, of course, a separate matter. ↩